Blog posts

Posts

A Hackers Manifesto, verze 4.0, kapitola 4.

By samotar, 10 January 2023

Alfred ve dvoře čili Poznámka k pražské hetero-utopii

By samotar, 10 November 2022

Trnovou korunou a tankem do srdíčka

By samotar, 2 July 2022

Hakim Bey - Informační válka

By samotar, 26 March 2022

Jean-Pierre Dupuy: Do we shape technologies, or do they shape us?

By samotar, 6 March 2022

Václav Cílek: Záhada zpívající houby

By samotar, 15 February 2022

Guy Debord - Teorie dérive

By samotar, 21 January 2022

Jack Burnham – Systémová estetika

By samotar, 19 November 2021

Poznámka pod čarou k výstavě Handa Gote: Věc, nástroj, čas, fetiš, hygiena, tabu

By samotar, 13 July 2021

Rána po ránech

By samotar, 23 May 2021

Na dohled od bronzového jezdce

By samotar, 4 March 2021

Z archivu:Mlha - ticho - temnota a bílé díry

By samotar, 7 October 2020

Zarchivu: Hůlna-kejdže

By samotar, 7 September 2020

Center for Land Use Interpretation

By samotar, 18 June 2020

Dawn Chorus Day - zvuky za svítání

By samotar, 30 April 2020

Z archivu: Bílé Břehy 2012 a Liběchov 2011

By , 3 April 2020

Z archivu: Krzysztof Wodiczko v DOXU

By samotar, 26 March 2020

GARY SNYDER: WRITERS AND THE WAR AGAINST NATURE

By samotar, 20 March 2020

Podoby domova: hnízda, nory, doupata, pavučiny, domestikace a ekologie

By samotar, 17 March 2020

Michel Serres: Transdisciplinarity as Relative Exteriority

By samotar, 5 November 2019

Pavel Ctibor: Sahat zakázáno

By samotar, 22 September 2019

Emmanuel Lévinas: HEIDEGGER, GAGARIN A MY

By samotar, 19 September 2019

Atmosférické poruchy / Atmospheric Disturbances - Ustí nad Labem

By samotar, 13 September 2019

Erkka Laininen: A Radical Vision of the Future School

By samotar, 10 August 2019

Anton Pannekoek: The Destruction of Nature (1909)

By samotar, 21 July 2019

Co padá shůry - světlo, pelyněk, oheň a šrot

By samotar, 30 December 2018

2000 slov v čase klimatických změn - manifest

By samotar, 2 November 2018

Vladimír Úlehla, sucho, geoinženýrství, endokrinologie, ekologie a Josef Charvát

By samotář, 22 September 2018

Lukáš Likavčan: Thermodynamics of Necrocracy - SUVs, entropy, and contingency management

By samotar, 20 July 2018

Tajemství spolupráce: Miloš Šejn

By samotar, 27 June 2018

Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You) Trevor Paglen

By samotar, 2 June 2018

KŘEST KNIHY KRAJINA V POZORU: THE LANDSCAPE IN FOCUS.

By samotar, 18 May 2018

Případ zchudlé planety:Vojtěch Kotecký

By samotar, 22 April 2018

Rozhovor na Vltavě: Jak umění reaguje na dobu antropocénu?

By samotar, 10 March 2018

Skolt Sámi Path to Climate Change Resilience

By samotar, 10 December 2017

Brian Holmes: Driving the Golden Spike - The Aesthetics of Anthropocene Public Space

By samotar, 22 November 2017

Ohlédnutí/Revisited Soundworm Gathering

By samotař, 9 October 2017

Kleté krajiny

By samotar, 7 October 2017

Kinterova Jednotka a postnatura

By samotař, 15 September 2017

Ruiny-Černý trojúhelník a Koudelkův pohyb v saturnských kruzích

By samotar, 13 July 2017

Upsych316a Universal Psychiatric Church

By Samotar, 6 July 2017

Miloš Vojtěchovský: Krátká rozprava o místě z roku 1994

By milos, 31 May 2017

Za teorií poznání (radostný nekrolog), Bohuslav Blažek

By miloš vojtěchovský, 9 April 2017

On the Transmutation of Species

By miloš vojtěchovský, 27 March 2017

Gustav Metzger: Poznámky ke krizi v technologickém umění

By samotař, 2 March 2017

CYBERPOSITIVE, Sadie Plant a Nick Land

By samotař, 2 March 2017

Ivan Illich: Ticho jako obecní statek

By samotař, 18 February 2017

Dialog o primitivismu – Lawrence Jarach a John Zerzan

By samotar, 29 December 2016

Thomas Berry:Ekozoická éra

By samotař, 8 December 2016

Jason W. Moore: Name the System! Anthropocenes & the Capitalocene Alternative

By miloš vojtěchovský, 24 November 2016

Michel Serres: Revisiting The Natural Contract

By samotař, 11 November 2016

Best a Basta době uhelné

By samotař, 31 October 2016

Epifanie, krajina a poslední člověk/Epiphany, Landscape and Last Man

By Samotar, 20 October 2016

Doba kamenná - (Ein, Eisen, Wittgen, Frankenstein), doba plastová a temná mineralogie

By samotař, 4 October 2016

Hledání hlasu řeky Bíliny

By samotař, 23 September 2016

Harrisons: A MANIFESTO FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

By , 19 September 2016

T.J. Demos: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Gynocene: The Many Names of Resistance

By , 11 September 2016

Bratrstvo

By samotař, 1 September 2016

Neptunismus a plutonismus na vyhaslé sopce Bořeň

By , 14 August 2016

Murray Bookchin: Toward an Ecological Society/ K ekologické společnosti (1974)

By samotař, 31 July 2016

Metafory, endofyzika, manželé Themersonovi a Gordon Pask

By samotař, 15 July 2016

Anima Mundi Revisited

By miloš vojtěchovský, 28 June 2016

Simon A. Levin: The Evolution of Ecology

By samotař, 21 June 2016

Anna Remešová: Je možné představit si změnu?

By samotar, 20 June 2016

Jan Hloušek: Uranové město

By samotař, 31 May 2016

Josef Šmajs: Složí lidstvo zkoušku své racionální dospělosti?

By samotař, 20 May 2016

Manifest The Dark Mountain Project

By Samotar, 3 May 2016

Pokus o popis jednoho zápasu

By samotar, 29 April 2016

Václav Cílek: Antropocén – velké zrychlení světa

By Slawomír Uher, 23 April 2016

Nothing worse or better can happen

By Ewa Jacobsson, 5 April 2016

Real Reason we Can’t Stop Global Warming: Saskia Sassen

By , 18 March 2016

The Political Economy of the Cultural Commons and the Nature of Sustainable Wealth

By samotar, 12 March 2016

Jared Diamond - Easter's End

By , 21 February 2016

Felix Guattari - Three Ecologies (part 1)

By , 19 February 2016

W. H. Auden: Journey to Iceland

By , 9 February 2016

Jussi Parikka: The Earth

By Slawomír Uher, 8 February 2016

Brian Holmes: Extradisciplinary Investigations. Towards a New Critique of Institutions

By Stanislaw, 7 February 2016

Co číhá za humny? neboli revoluce přítomnosti

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 31 January 2016

Podivuhodný osud polárníka a malíře Julia Payera

By , 23 January 2016

Red Sky: The Eschatology of Trans

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 19 January 2016

#AKCELERACIONISTICKÝ MANIFEST (14. května 2013)

By samotar, 7 January 2016

The Forgotten Space: Notes for a Film

By , 7 January 2016

Rise and Fall of the Herring Towns:Impacts of Climate and Human Teleconnections

By , 25 December 2015

Hlubinná, temná, světlá i povrchová ekologie světa

By , 22 December 2015

Three short movies: Baroque Duchcov, New Lakes of Mostecko and Lignite Clouds

By Michal Kindernay, 21 December 2015

Lenka Dolanová: Umění mediální ekologie

By , 21 December 2015

Towards an Anti-atlas of Borders

By , 20 December 2015

Pavel Mrkus - KINESIS, instalace Nejsvětější Salvátor

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 6 December 2015

Tváře/Faces bez hranic/Sans Frontiers

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 29 November 2015

Josef Šmajs: Ústava Země/A Constitution for the Earth

By Samotar, 28 November 2015

John Jordan: The Work of Art (and Activism) in the Age of the Anthropocene

By Samotar, 23 November 2015

Humoreska: kočky, koulení, hroby a špatná muška prince Josefa Saského

By Samotar, 13 November 2015

Rozhovor:Před věčným nic se katalogy nesčítají

By Samotar, 11 November 2015

Lecture by Dustin Breiting and Vít Bohal on Anthropocene

By Samotar, 8 November 2015

Antropocén a mocné žblunknutí/Anthropocene and the Mighty Plop

By Samotar, 2 November 2015

Rory Rowan:Extinction as Usual?Geo-Social Futures and Left Optimism

By Samotar, 27 October 2015

Pavel Klusák: Budoucnost smutné krajiny/The Future of a Sad Region

By ll, 19 October 2015

Na Zemi vzhůru nohama

By Alena Kotzmannová, 17 October 2015

Upside-down on Earth

By Alena Kotzmannová, 17 October 2015

Thomas Hylland Eriksen: What’s wrong with the Global North and the Global South?

By Samotar, 17 October 2015

Nýey and Borealis: Sonic Topologies by Nicolas Perret & Silvia Ploner

By Samotar, 12 October 2015

Images from Finnmark (Living Through the Landscape)

By Nicholas Norton, 12 October 2015

Bruno Latour: Love Your Monsters, Why We Must Care for Our Technologies As We Do Our Children

By John Dee, 11 October 2015

Temné objekty k obdivu: Edward Burtynsky, Mitch Epstein, Alex Maclean, Liam Young

By Samotar 10 October 2015, 10 October 2015

Czech Radio on Frontiers of Solitude

By Samotar, 10 October 2015

Beyond Time: orka, orka, orka, nečas, nečas, nečas

By Samotar, 10 October 2015

Langewiese and Newt or walking to Dlouhá louka

By Michal Kindernay, 7 October 2015

Notice in the Norwegian newspaper „Altaposten“

By Nicholas Norton, 5 October 2015

Interview with Ivar Smedstad

By Nicholas Norton, 5 October 2015

Iceland Expedition, Part 2

By Julia Martin, 4 October 2015

Closing at the Osek Monastery

By Michal Kindernay, 3 October 2015

Iceland Expedition, Part 1

By Julia Martin, 3 October 2015

Finnmarka a kopce / The Hills of Finnmark

By Vladimír Merta, 2 October 2015

Od kláštera Osek na Selesiovu výšinu, k Lomu, Libkovicům, Hrdlovce a zpět/From The Osek Cloister to Lom and back

By Samotar, 27 September 2015

Sápmelažžat Picnic and the Exploration of the Sami Lands and Culture

By Vladimir, 27 September 2015

Gardens of the Osek Monastery/Zahrady oseckého kláštera

By ll, 27 September 2015

Workshop with Radek Mikuláš/Dílna s Radkem Mikulášem

By Samotářka Dagmar, 26 September 2015

Czech Radio Interview Jan Klápště, Ivan Plicka and mayor of Horní Jiřetín Vladimír Buřt

By ll, 25 September 2015

Bořeň, zvuk a HNP/Bořeň, sound and Gross National Product

By Samotar, 25 September 2015

Já, Doly, Dolly a zemský ráj

By Samotar, 23 September 2015

Up to the Ore Mountains

By Michal, Dagmar a Helena Samotáři , 22 September 2015

Václav Cílek and the Sacred Landscape

By Samotář Michal, 22 September 2015

Picnic at the Ledvice waste pond

By Samotar, 19 September 2015

Above Jezeří Castle

By Samotar, 19 September 2015

Cancerous Land, part 3

By Tamás Sajó, 18 September 2015

Ledvice coal preparation plant

By Dominik Žižka, 18 September 2015

pod hladinou

By Dominik Žižka, 18 September 2015

Cancerous Land, part 2

By Tamás Sajó, 17 September 2015

Cancerous Land, part 1

By Tamás Sajó, 16 September 2015

Offroad trip

By Dominik Žižka, 16 September 2015

Ekologické limity a nutnost jejich prolomení

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 16 September 2015

Lignite Clouds Sound Workshop: Days I and II

By Samotar, 15 September 2015

Recollection of Jezeří/Eisenberg Arboretum workshop

By Samotar, 14 September 2015

Walk from Mariánské Radčice

By Michal Kindernay, 12 September 2015

Mariánské Radčice and Libkovice

By Samotar, 11 September 2015

Tušimice II and The Vicarage, or the Parsonage at Mariánské Radčice

By Samotar, 10 September 2015

Most - Lake, Fish, algae bloom

By Samotar, 8 September 2015

Monday: Bílina open pit excursion

By Samotar, 7 September 2015

Duchcov II. - past and tomorrow

By Samotar, 6 September 2015

Duchcov II.

By Samotar, 6 September 2015

Arrival at Duchcov I.

By Samotar, 6 September 2015

Poznámka k havárii rypadla KU 300 (K severu 1)

By Samotar, 19 August 2015

On the Transmutation of Species

Today, there is an industrial mutation — a technological mutation — that’s taking place. New machines are appearing: cognitive machines, cultural machines, and now nanotechnologies. There are new processes of exteriorisation: Artificial Intelligence, the cell phone. … Until today, these technologies of exteriorization were limited to the world of Research and Development. Now, they are expanding into consumer society at large.

—Bernard Stiegler

From the vantage point of geological time it seems the moment had occurred just yesterday. Humanity awoke from a dreamtime and started learning more than just to observe: to construct, improve and dismantle sophisticated systems and visual apparatuses; to obtain, distinguish, scan, save, replicate, multiply and compare the images of the world and of the human from above, from a bird’s-eye view. Today the ever- expanding content of the imagosphere’s digital central archive contains terabytes of landscapes, close-ups, sketches, samples, portraits, self-portraits, but also images which are created autopoietically and without the active involvement of a human: the image database of stratigraphic, geo-morphological and geo-historical data and records.

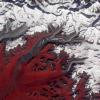

Such archives also offer us both direct and circumstantial evidence. Apart from prehistoric images, we also find forensic documentation on the extinction of species — eschatological illustrations and whole files on the exploitation and colonization of the biosphere by the human. The screens and monitors clearly show the development of new tissues of informational networks, as well as the agglomerations which surround and connect our terrestrial cities. These archives also allow us to animate other processes of urbanization, and observe the changes in the planet’s color palette — the frontier between desert and vegetation, the melting of polar ice, and the development of sprawling industrial zones. We can observe the pulsing capillaries fed by the system’s obsessive compulsion to endlessly transfer resources, goods and nutrients, and to dig up and rearrange fossils and accelerate their metamorphosis into energy, heat and smog.

By means of satellite cameras and drones, people have claimed the surface of the Earth and have gained the ability to perceive the world from a bird’s-eye view. The art of objective distance transforms the appearance of our homes, changes our perception of planetary topography, and transforms space into a living map — a fragmented image complex compiled by immersive apparatuses of ever-present observation. The observation post is the avatar of today’s world — it is a metalab, a planetary dump where horizons open up onto distant space, and where contours and details are obfuscated by the granularity of LCD monitors and the electromagnetic noise of data.

Thanks to tools, the people of the 21st century see not only far, but also deep into physical matter, observing processes which their ancestors could only intuit. We can observe and study new natural and artificial formations and structures, circumscribe vast environments with meandering rivers and zones of lithium tailing ponds, seacoast fractals, cloud voyages, and networks constructed at a speed and scale never before seen. Man’s drive towards energy production has changed even the appearance of the Earth. As an image from Athanasius Kircher’s The Ecstatic Journey (Itinerarium Exstaticum, 1656, Rome), a visionary tale documenting a round-trip to the planets, electric plants and grids have obsolesced the rhythms of day and night and have illuminated vast continents, whose shining dendrites and fibres may be seen from outer space.

Humanity’s bird’s-eye view does not necessarily have to be spectacular, pleasant or entertaining. If we conquer our vertigo, we will often see scenery that is rather bleak or unsettling. Throughout the ages, people have largely remained hidden, prowling the bush and forests, mapping the immediate surroundings and the earth beneath their feet, while turning their eyes to the heavens. The starry sky has always been the primeval screen for projecting earthly anxieties; it was a stage for magical thinking, instances of pareidolia and evocations. The heavenly optics of the Anthropocene, however, offer views of complex systemic events and processes of which, until recently, we could detect only small details. We were either unaware of their wider existence, or did not ascribe any importance to them. Now, we are thrust into the roles of both observer and actor in planetary changes.

The Trees of Life

The era stretching from the medieval cosmologies to 19th-century positivist science was rife with attempts at abstracting a coherent system — a mental and descriptive visualization of reality — which fed the imagination of artists and the experimentation of natural scientists. Each period found and established some type of successful unifying diagram which corresponded to the vision, ideologies, situations, and scientific knowledge present at that specific time and place. In Darwin’s The Origin of Species (6th edition, 1872) we find the following paragraph (which was clearly inspired by a sketch from his B notebook Transmutation of Species, dated 1837):

The affinities of all beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth. The green and budding twigs may represent existing species; and those produced during former years may represent the long succession of extinct species. … As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever-branching and beautiful ramifications.

Ernst Haeckel, who was largely devoted to popularizing Darwin’s work, published a similarly — but much more “realistic” Darwinian diagram in his Evolution of Man in1866. It is a popular picture of a “phylogenetic” tree which further promulgated the idea of an evolutionary development of life and the taxa joined together are implied to have descended from a common ancestor. The roots of a grown oak, representing the emergence of life and the taxonomy of simple organisms (protozoa), branch upwards in a unitary gesture of development towards the genus, species and family. The branches shoot up towards more complex forms — plants, fungi, vertebrates, mammals — and the very pinnacle of God’s work is crowned by the “Kingdom of Man”.

The 20th century gradually developed and dispelled many of the outdated ideas and seemingly obsolete images of how humanity imagined the world. Some conceptions were embedded within the morphology and models of live matter which developed from still older constructs of natural science and religion. The colorful illustrated tableaux of marine life in Haeckel’s encyclopedias exhibit a fin-de-siècle aesthetic and have an affinity with the organic morphology of the Jugendstil. This neo-baroque filigree geometry of mysterious marine crustaceans was markedly popular towards the end of the 19th century. Later, it resonated with artists associated with Bauhaus, such as Paul Klee, as well as fermenting the imaginative unconscious of the Surrealists, and later still was an influence on Buckminster Fuller’s architectonic principle of Dymaxion. It was Donald B. Ingber, the director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, who took up Buckminster Fuller’s and sculptor Kenneth Snelson’s concept of tensegrity (tensional integrity) which, in bionic architecture, forms the underlying concept of hierarchically organized and spatially regular organic structures. According to the theory the basic expression of organized living matter is its ability to resist gravity. The formation of firm organs, such as bones, tendons and muscles, is predicated on this tectonic principle of tension. The extracellular matrix organizes cells into tissue, and the cells adjust and retain their shape based on the cytoskeleton scaffolding which is manifest both at the macro and the micro, or molecular, scale.

The domain of machine and non-machine non-humans (the unhuman in my terminology) joins people in the building of the artifactual collective called nature. None of these actants can be considered as simply resource, ground, matrix, object, material, instrument, frozen labor; they are all more unsettling than that.

—The Promises of Monsters, Donna Haraway

This structural characteristic which attempts to find a homology between the micro and macro worlds, between different human and “unhuman” systems was also being developed in other disciplines. Around the middle of the previous century cybernetics, system theory, anthropology, and other social and natural sciences were proposing alternative models of basic biological and physical phenomena, such as open and mutually connected systems which strive to retain homeostasis by means of feedback loops and adaptation, thus resisting entropic processes. The concept of a ‘rhizomatic structure’ received much attention. This irregular and seemingly chaotic shape does not heed the determinacy of gravity, or hierarchical formations of growth and linearity.

Deleuze and Guattari borrowed the term ‘rhizome’ from biologist and cybernetician Gregory Bateson.They describe it as a symptom of heterogeneity; as a subversive alternative to the patriarchal archetype of the tree. Thus they expanded its relevance from the language of botany and natural sciences into fields such as linguistics, ideology and aesthetics:

We are tired of the tree. We must no longer put our faith in trees, roots, or radicals; we have suffered enough from them. The whole arborescent culture is founded on them, from biology to linguistics. On the contrary, only underground stems and aerial roots, the adventitious and the rhizome are truly beautiful, loving or political. [Deleuze & Guattari, Capitalism and Schizophrenia, 1983].

The rhizome is the determining shape of ginger, calamus and the potato plant, the shape of the labyrinthine system of paths and walls of the termite nest, silicon-based electronic and electric networks, moss, parasitic and symbiotic mycelia connected by trace elements in soil, tree roots and animal biotopes — all these are connected in one branching organism. Its propagators further ascribed to it an essential affinity with the postindustrial techno-culture typified by crumbling boundaries between the public and the private, biological and technological, organic and inorganic, and between the center and periphery. The rhizome is thus considered as a universal element, and a significant concept in natural, artificial, sublime, hermetic and non-linear figures. No organ is the ultimate beginning or end, nor is it the cause or effect. We cannot find axial symmetries, a center, or a periphery. The rhizomatic organism has a diffuse intelligence: everywhere it simultaneously moves, gives birth, grows and perishes. Consequently, this kind of evolution resembles a clump of roots that considers the occurrence of multiplicities. Emerging species grow from the rhizome with gene repertoires of various origins allowing the multiplication and perpetuation of this species. As such, new species and new genes are and will continuously appear.

Naturally, I had no way of controlling the form of what I was making: I just stayed there all huddled up, silent and sluggish, and I secreted. I went on even after the shell covered my whole body.

—Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino

We find rhizomes not only in the world of fungi, insects but also in moss and lichen. Lichens are able to penetrate into various substrates, and are most often found on rocks, in soil and as epiphytes growing on trees and bushes, comprising one part of a symbiotic community of fungi (a mycobiont) and algae or cyanobacteria (a photo- or phycobiont). Their relationships stretch from the mutually beneficial to the clearly parasitic. Their commensalism is predicated on the biological cohabitation between two organisms where one reaps benefits while the other remains unaffected. The model of allelopathy or antibiosis however, describes the relationship when one species of organism negatively affects its surroundings or other species by means of chemicals which it releases into the environment. Such an analogy offers an ominous model for the Anthropocene. The „natural history“ and new aesthetics of electronic fossils is indicative of the economies, cultures and ecologies of our time. Omnipresent digital debris penetrate as artificial lichens into geological subtrates and into bodies of living organism. Its rhizomatic structures are unfolding through minerals, chemicals, temporalities, soil, water, air.

Krištof Kintera’s “post-natural” works and installations are predicated upon the counterpoint of the sculpture’s rhizomatic anatomy with the orthogonal geometry of the aseptic gallery space. As if the toxic hardware virus crawling on the floor were affected by mutagenesis which shaped its sculpture-organisms’s biomorphic, yet inorganic body made of e-waste, digital debris, copper and silicone. The appearance remains enigmatic — perhaps the viewer is watching the remains of a symbiont’s exoskeleton, or an artifact from an unknown insectoid civilization, a model of post-apocalyptic architecture, or a fossil of a species from the electronic age.

Miloš Vojtěchovský, text for the catalogue of Kristof Kintera´s large installation POSTNATURLIA at the Colezione Maramotti, 2017, translation Vít Bohal