Blog posts

Posts

A Hackers Manifesto, verze 4.0, kapitola 4.

By samotar, 10 January 2023

Alfred ve dvoře čili Poznámka k pražské hetero-utopii

By samotar, 10 November 2022

Trnovou korunou a tankem do srdíčka

By samotar, 2 July 2022

Hakim Bey - Informační válka

By samotar, 26 March 2022

Jean-Pierre Dupuy: Do we shape technologies, or do they shape us?

By samotar, 6 March 2022

Václav Cílek: Záhada zpívající houby

By samotar, 15 February 2022

Guy Debord - Teorie dérive

By samotar, 21 January 2022

Jack Burnham – Systémová estetika

By samotar, 19 November 2021

Poznámka pod čarou k výstavě Handa Gote: Věc, nástroj, čas, fetiš, hygiena, tabu

By samotar, 13 July 2021

Rána po ránech

By samotar, 23 May 2021

Na dohled od bronzového jezdce

By samotar, 4 March 2021

Z archivu:Mlha - ticho - temnota a bílé díry

By samotar, 7 October 2020

Zarchivu: Hůlna-kejdže

By samotar, 7 September 2020

Center for Land Use Interpretation

By samotar, 18 June 2020

Dawn Chorus Day - zvuky za svítání

By samotar, 30 April 2020

Z archivu: Bílé Břehy 2012 a Liběchov 2011

By , 3 April 2020

Z archivu: Krzysztof Wodiczko v DOXU

By samotar, 26 March 2020

GARY SNYDER: WRITERS AND THE WAR AGAINST NATURE

By samotar, 20 March 2020

Podoby domova: hnízda, nory, doupata, pavučiny, domestikace a ekologie

By samotar, 17 March 2020

Michel Serres: Transdisciplinarity as Relative Exteriority

By samotar, 5 November 2019

Pavel Ctibor: Sahat zakázáno

By samotar, 22 September 2019

Emmanuel Lévinas: HEIDEGGER, GAGARIN A MY

By samotar, 19 September 2019

Atmosférické poruchy / Atmospheric Disturbances - Ustí nad Labem

By samotar, 13 September 2019

Erkka Laininen: A Radical Vision of the Future School

By samotar, 10 August 2019

Anton Pannekoek: The Destruction of Nature (1909)

By samotar, 21 July 2019

Co padá shůry - světlo, pelyněk, oheň a šrot

By samotar, 30 December 2018

2000 slov v čase klimatických změn - manifest

By samotar, 2 November 2018

Vladimír Úlehla, sucho, geoinženýrství, endokrinologie, ekologie a Josef Charvát

By samotář, 22 September 2018

Lukáš Likavčan: Thermodynamics of Necrocracy - SUVs, entropy, and contingency management

By samotar, 20 July 2018

Tajemství spolupráce: Miloš Šejn

By samotar, 27 June 2018

Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You) Trevor Paglen

By samotar, 2 June 2018

KŘEST KNIHY KRAJINA V POZORU: THE LANDSCAPE IN FOCUS.

By samotar, 18 May 2018

Případ zchudlé planety:Vojtěch Kotecký

By samotar, 22 April 2018

Rozhovor na Vltavě: Jak umění reaguje na dobu antropocénu?

By samotar, 10 March 2018

Skolt Sámi Path to Climate Change Resilience

By samotar, 10 December 2017

Brian Holmes: Driving the Golden Spike - The Aesthetics of Anthropocene Public Space

By samotar, 22 November 2017

Ohlédnutí/Revisited Soundworm Gathering

By samotař, 9 October 2017

Kleté krajiny

By samotar, 7 October 2017

Kinterova Jednotka a postnatura

By samotař, 15 September 2017

Ruiny-Černý trojúhelník a Koudelkův pohyb v saturnských kruzích

By samotar, 13 July 2017

Upsych316a Universal Psychiatric Church

By Samotar, 6 July 2017

Miloš Vojtěchovský: Krátká rozprava o místě z roku 1994

By milos, 31 May 2017

Za teorií poznání (radostný nekrolog), Bohuslav Blažek

By miloš vojtěchovský, 9 April 2017

On the Transmutation of Species

By miloš vojtěchovský, 27 March 2017

Gustav Metzger: Poznámky ke krizi v technologickém umění

By samotař, 2 March 2017

CYBERPOSITIVE, Sadie Plant a Nick Land

By samotař, 2 March 2017

Ivan Illich: Ticho jako obecní statek

By samotař, 18 February 2017

Dialog o primitivismu – Lawrence Jarach a John Zerzan

By samotar, 29 December 2016

Thomas Berry:Ekozoická éra

By samotař, 8 December 2016

Jason W. Moore: Name the System! Anthropocenes & the Capitalocene Alternative

By miloš vojtěchovský, 24 November 2016

Michel Serres: Revisiting The Natural Contract

By samotař, 11 November 2016

Best a Basta době uhelné

By samotař, 31 October 2016

Epifanie, krajina a poslední člověk/Epiphany, Landscape and Last Man

By Samotar, 20 October 2016

Doba kamenná - (Ein, Eisen, Wittgen, Frankenstein), doba plastová a temná mineralogie

By samotař, 4 October 2016

Hledání hlasu řeky Bíliny

By samotař, 23 September 2016

Harrisons: A MANIFESTO FOR THE 21ST CENTURY

By , 19 September 2016

T.J. Demos: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Gynocene: The Many Names of Resistance

By , 11 September 2016

Bratrstvo

By samotař, 1 September 2016

Neptunismus a plutonismus na vyhaslé sopce Bořeň

By , 14 August 2016

Murray Bookchin: Toward an Ecological Society/ K ekologické společnosti (1974)

By samotař, 31 July 2016

Metafory, endofyzika, manželé Themersonovi a Gordon Pask

By samotař, 15 July 2016

Anima Mundi Revisited

By miloš vojtěchovský, 28 June 2016

Simon A. Levin: The Evolution of Ecology

By samotař, 21 June 2016

Anna Remešová: Je možné představit si změnu?

By samotar, 20 June 2016

Jan Hloušek: Uranové město

By samotař, 31 May 2016

Josef Šmajs: Složí lidstvo zkoušku své racionální dospělosti?

By samotař, 20 May 2016

Manifest The Dark Mountain Project

By Samotar, 3 May 2016

Pokus o popis jednoho zápasu

By samotar, 29 April 2016

Václav Cílek: Antropocén – velké zrychlení světa

By Slawomír Uher, 23 April 2016

Nothing worse or better can happen

By Ewa Jacobsson, 5 April 2016

Real Reason we Can’t Stop Global Warming: Saskia Sassen

By , 18 March 2016

The Political Economy of the Cultural Commons and the Nature of Sustainable Wealth

By samotar, 12 March 2016

Jared Diamond - Easter's End

By , 21 February 2016

Felix Guattari - Three Ecologies (part 1)

By , 19 February 2016

W. H. Auden: Journey to Iceland

By , 9 February 2016

Jussi Parikka: The Earth

By Slawomír Uher, 8 February 2016

Brian Holmes: Extradisciplinary Investigations. Towards a New Critique of Institutions

By Stanislaw, 7 February 2016

Co číhá za humny? neboli revoluce přítomnosti

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 31 January 2016

Podivuhodný osud polárníka a malíře Julia Payera

By , 23 January 2016

Red Sky: The Eschatology of Trans

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 19 January 2016

#AKCELERACIONISTICKÝ MANIFEST (14. května 2013)

By samotar, 7 January 2016

The Forgotten Space: Notes for a Film

By , 7 January 2016

Rise and Fall of the Herring Towns:Impacts of Climate and Human Teleconnections

By , 25 December 2015

Hlubinná, temná, světlá i povrchová ekologie světa

By , 22 December 2015

Three short movies: Baroque Duchcov, New Lakes of Mostecko and Lignite Clouds

By Michal Kindernay, 21 December 2015

Lenka Dolanová: Umění mediální ekologie

By , 21 December 2015

Towards an Anti-atlas of Borders

By , 20 December 2015

Pavel Mrkus - KINESIS, instalace Nejsvětější Salvátor

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 6 December 2015

Tváře/Faces bez hranic/Sans Frontiers

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 29 November 2015

Josef Šmajs: Ústava Země/A Constitution for the Earth

By Samotar, 28 November 2015

John Jordan: The Work of Art (and Activism) in the Age of the Anthropocene

By Samotar, 23 November 2015

Humoreska: kočky, koulení, hroby a špatná muška prince Josefa Saského

By Samotar, 13 November 2015

Rozhovor:Před věčným nic se katalogy nesčítají

By Samotar, 11 November 2015

Lecture by Dustin Breiting and Vít Bohal on Anthropocene

By Samotar, 8 November 2015

Antropocén a mocné žblunknutí/Anthropocene and the Mighty Plop

By Samotar, 2 November 2015

Rory Rowan:Extinction as Usual?Geo-Social Futures and Left Optimism

By Samotar, 27 October 2015

Pavel Klusák: Budoucnost smutné krajiny/The Future of a Sad Region

By ll, 19 October 2015

Na Zemi vzhůru nohama

By Alena Kotzmannová, 17 October 2015

Upside-down on Earth

By Alena Kotzmannová, 17 October 2015

Thomas Hylland Eriksen: What’s wrong with the Global North and the Global South?

By Samotar, 17 October 2015

Nýey and Borealis: Sonic Topologies by Nicolas Perret & Silvia Ploner

By Samotar, 12 October 2015

Images from Finnmark (Living Through the Landscape)

By Nicholas Norton, 12 October 2015

Bruno Latour: Love Your Monsters, Why We Must Care for Our Technologies As We Do Our Children

By John Dee, 11 October 2015

Temné objekty k obdivu: Edward Burtynsky, Mitch Epstein, Alex Maclean, Liam Young

By Samotar 10 October 2015, 10 October 2015

Czech Radio on Frontiers of Solitude

By Samotar, 10 October 2015

Beyond Time: orka, orka, orka, nečas, nečas, nečas

By Samotar, 10 October 2015

Langewiese and Newt or walking to Dlouhá louka

By Michal Kindernay, 7 October 2015

Notice in the Norwegian newspaper „Altaposten“

By Nicholas Norton, 5 October 2015

Interview with Ivar Smedstad

By Nicholas Norton, 5 October 2015

Iceland Expedition, Part 2

By Julia Martin, 4 October 2015

Closing at the Osek Monastery

By Michal Kindernay, 3 October 2015

Iceland Expedition, Part 1

By Julia Martin, 3 October 2015

Finnmarka a kopce / The Hills of Finnmark

By Vladimír Merta, 2 October 2015

Od kláštera Osek na Selesiovu výšinu, k Lomu, Libkovicům, Hrdlovce a zpět/From The Osek Cloister to Lom and back

By Samotar, 27 September 2015

Sápmelažžat Picnic and the Exploration of the Sami Lands and Culture

By Vladimir, 27 September 2015

Gardens of the Osek Monastery/Zahrady oseckého kláštera

By ll, 27 September 2015

Workshop with Radek Mikuláš/Dílna s Radkem Mikulášem

By Samotářka Dagmar, 26 September 2015

Czech Radio Interview Jan Klápště, Ivan Plicka and mayor of Horní Jiřetín Vladimír Buřt

By ll, 25 September 2015

Bořeň, zvuk a HNP/Bořeň, sound and Gross National Product

By Samotar, 25 September 2015

Já, Doly, Dolly a zemský ráj

By Samotar, 23 September 2015

Up to the Ore Mountains

By Michal, Dagmar a Helena Samotáři , 22 September 2015

Václav Cílek and the Sacred Landscape

By Samotář Michal, 22 September 2015

Picnic at the Ledvice waste pond

By Samotar, 19 September 2015

Above Jezeří Castle

By Samotar, 19 September 2015

Cancerous Land, part 3

By Tamás Sajó, 18 September 2015

Ledvice coal preparation plant

By Dominik Žižka, 18 September 2015

pod hladinou

By Dominik Žižka, 18 September 2015

Cancerous Land, part 2

By Tamás Sajó, 17 September 2015

Cancerous Land, part 1

By Tamás Sajó, 16 September 2015

Offroad trip

By Dominik Žižka, 16 September 2015

Ekologické limity a nutnost jejich prolomení

By Miloš Vojtěchovský, 16 September 2015

Lignite Clouds Sound Workshop: Days I and II

By Samotar, 15 September 2015

Recollection of Jezeří/Eisenberg Arboretum workshop

By Samotar, 14 September 2015

Walk from Mariánské Radčice

By Michal Kindernay, 12 September 2015

Mariánské Radčice and Libkovice

By Samotar, 11 September 2015

Tušimice II and The Vicarage, or the Parsonage at Mariánské Radčice

By Samotar, 10 September 2015

Most - Lake, Fish, algae bloom

By Samotar, 8 September 2015

Monday: Bílina open pit excursion

By Samotar, 7 September 2015

Duchcov II. - past and tomorrow

By Samotar, 6 September 2015

Duchcov II.

By Samotar, 6 September 2015

Arrival at Duchcov I.

By Samotar, 6 September 2015

Poznámka k havárii rypadla KU 300 (K severu 1)

By Samotar, 19 August 2015

Upsych316a Universal Psychiatric Church

Opera Omnia by The Peerless Cooperative of the Holy Nurture

This brief outline of The Peerless Cooperative of the Holy Nurture (JSD) attempts to shed new light on the activities of this group, its programs and artistic miscellanea examined from within the realm of fine art, and seeks to establish connections with some parallel tendencies. This text is also a humble attempt to increase public awareness of the rarefied history of the Cooperative. The text was originally written by Miloš Vojtěchovský around 2008 upon the nomination of the JSD for the Jindřich Chalupecký Award (which the Cooperative ultimately did not receive) and was updated to its current form in 2017 for the Agosto Foundation Mediateka.

As will be shown, the framing the Cooperative as “outsider art” or “non-art” within a context of art may result in a distortion of the values, goals and meanings of the Collective. This overview of Upsych activities is mostly preoccupied with the founding and building the Church of Upsych316a, a large-format social art work devoted purely to the worship of the Holy Scrap, which is intended for use in the cultivation of art therapy, and thus the redemption of man through the faculties of the imagination.

A Brief Outline of the Activities of the Peerless Cooperative of the Holy Nurture (JSD) and The History of The Construction of The Temple of Artistic Blasphemy, devoted to the worship and care of The Holy Scrap with the Goal of Cultivating and Fostering the Art-therapeutic and Artistic Imagination.

It is thus, in this domiciliation, in this house arrest, that archives take place. The dwelling, this place where they dwell permanently, marks this institutional passage from the private to the public, which does not always mean from the secret to the non-secret.…

From Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression by Jacques Derrida.

The JSD cooperative and the ŠŠ Unit (Jednotka Špružení Šmelcu / The Unit of the Holy Scrap) knit together the conceptual founders and representative dignitaries – Chairman and Deputy, the brothers David and Martin Koutecký – and a loose community of “collaborators”, friends, supporters, allied art groups and fans. Both “organisations” have attained minimal-to-no fame on the Czech contemporary art scene. Perhaps that is because they operate on the boundary between art and life. As very few references to the JSD Cooperative can be found in arts literature, journals, the mass media or the press — no more in 2017 tha in 2008 — most of the resources used here are drawn from the files, collections, documents and archives of the Cooperative itself — the bulk of which documents public encounters with their curious events and activities. We thus must make do with our discoveries from field research, or oral testimonies from the actors and participants themselves. 1

According to its Statutes, the JSD Cooperative was “… founded on the night of January 12, 2001 solely for the purpose of nurturing and supporting by all means the Reason and the Cause – Mr. Miláček – the Young Holy, the Greatest Artist and the Biggest Love, and for the nurturing and development of Holiness in general.” According to this story, the tool for this peculiar assortment of activities necessitated the development of an “ever-growing bureaucratic apparatus and a strong hierarchy based on numerous executive sections, departments and committees.” This focus resulted in the most ambitious achievement of the JSD: the establishment and operation of the Universal Psychiatric Church 316a (Upsych – Universální Psychiatrický Chrám).

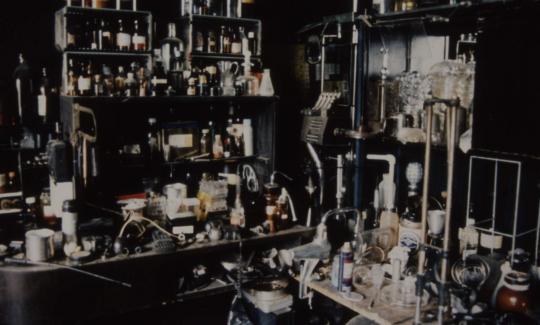

The Universal Psychiatric Church is located in a small town in northeast Bohemia in a 14th-century Gothic fortress purchased from the Czech Army in 1997 and subsequently occupied by the Cooperative. Though the labyrinthine fortress was in a deplorable condition, its new owners saved it from demolition, and its four floors have gradually become the repository (and victim) of a horde of surplus found objects, debris and scrap (the etymology of this term is “scrap, useless metal, filings”); some of it rare and antique, most of it worthless; but all of which has been obsessively accumulated over the past 15 years by the JSD’s ŠŠ Unit. The collection has been selected, expanded and recast with a specific purpose: to serve and fulfill the needs of approximately 40 (both fictional and “real”) tenants. Each inmate of Upsych Temple is treated as a unique “psychiatric case” and each acquires a specific story transcribed into the shape and furniture of each room. The intention is to provide the “tenants” with an “alternative” to the current forms of psychiatric care. The characters in this conceptual “staged drama” have their own dedicated rooms or spaces, and their “… psychic anomalies are not viewed as malfunctions to be cured but, on the contrary, are considered as faculties worthy of cultivating.” The entire stage design of the fortress, from the ground to the attic, is carefully composed so that it reflects the current mental state of the inmates. This creates the impression of a picturesque nstitute, one which recalls the one in the 1973 Polish film The Hourglass Sanatorium (Sanatorium pod klepsydrą, directed by Wojciech Jerzy Has, 1973) — but, in this case, without actors.

The Church is meticulously and diligently maintained by the Cooperative (as well as the ŠŠ Unit and the General Staff of the Geist — another related, but autonomous institution that secures the operation of Upsych). The occasional visitor is exposed to a neo-Merzbau architectural assemblage, a new embodiment of the House of Usher or a punk gesamtkunstwerk. But only through personal experience can one truly encounter the philosophy, eschatology, taxonomy and poetics of the JSD. 2

The vocabulary, hagiography, epiphany and idiosyncrasy of the Peerless Cooperative of the Holy Nurture suggest a variety of allusions to institutional, bureaucratic and ideological systems, including Christianity, religious syncretism, cosmology, literature, philosophy, alchemy, hermeticism, antique collecting, travelogues, modern art, architecture, cinema, theater, music, environmentalism, and the military. It combines the sacred and the mundane, Pop and underground, counter-culture and and hyper-postmodernism.

Trying to use ordinary critical reasoning to interpret and reveal the essence of the Cooperative’s methods and strategies by making recourse to the standard discourse of critique is not appropriate, as their methods are complex, baroque, and chaotic. Although the JSD can be seen as marginal epiphenomenon in contemporary Czech art and culture, its traits, methods and attitudes offer a wealth of opportunities for interpretation and comparison with current international and local cultural environments, both explicit and implicit.3

This initial survey of a few fragments of their writings, regulations, statements and other documents offers a small sample of the Cooperative’s multilayered identity, self-mythologization and attitudes toward its own work and life. But why therefore, after 15 years, the activities of JSD and Upsych still linger beyond the interest of both the public and the professional communities?

Between Private and Public

It is said that Maurice Blanchot, the enigmatic French writer and philosopher, refused to be photographed and firmly believed that the public shouldn’t be able to recognise his face. As a result, Blanchot achieved an almost inconceivable status: he prevented his face, identity and ego from colliding with his work (Samuel Beckett or Thomas Pynchon harbor a similar shyness for being photographed or appearing in the public eye).5

Nevertheless, an internet search for images of the author locates at least 18 photographs containing Blanchot’s face among the 17,000 results for images related to him. At the dawn of the 21st century, the need to carefully preserve one’s privacy in the face of a growing, omnipresent, and expanding public domain mirrors the turbulent battle between the hidden and the exposed, between the sacred and the profane. Typing the three letters G-O-D – the global quintessence of human religious belief – into the Google search engine returns more than six million results in a sliver of time, 0.16 seconds. Confronted with a cyberspace that now permeates the planet, the traditional concepts of sacred and profane, and the private and the public are dissolving.

How does this relate to JSD and Upsych? My premise about the Cooperative is that they are neither a private nor a public body. Its membership mostly refers to general and social issues, but always through the prism of personal, “familial,” sometimes fictitious and sometimes factual narratives. The Cooperative is not part of the social habits of the contemporary art community, structured around the relationships between the producer/curator/gallerist/collector. The JSD and UPSYCH organism is instead composed of a network of friends, of individuals direcltly or vicariously involved or familiar with the Collective’s activities and narratives. Rather than producing and distributing artifacts, everything is devoted to “fostering and developing holiness in general.”

One of the main chapters of the Cooperative’s manifesto is a playful articulation of the “Holy” or the “Sacred” that seems to be directly inspired by the corpus of religious, mostly Catholic phraseology of the Holy Essence of God and other religious rituals. The Cooperative’s worship of its blasphemous idol (or former “guru”) “Mr. Miláček, the Young Holy, the great Why” stems from a casual encounter with a fellow student of Milan Knížák’s studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. This personal contact became the source of an associative chain reaction of poetic hagiography and rites of grotesque idolatry. The core of this is based in describing the psychosocial identity, habits, creative appearance and artistic qualities of their divine Guru (whose role in the activities has gradually become less important). The result is a unique archive of observations and documents concerning the object of their wry and amusing worship.

The dramatic style of the cult of the “Holy Artist” is likewise grounded in a genuine link with the community of institutionalised religion, as well as the grotesque rituals of the art community and totalitarian systems. The style of “spiritual art” practised today within the Catholic Church is far removed from the Cooperative’s aesthetic attitudes. In the Cooperative, the counterpart of the “Sacred and Secret” is the “Burlesque,” performed in a ludicrous and blasphemous style of the rituals and manifested in the design of the assemblages and performances. The extemporaneity of the surplus of gadgets, scenery, instruments, stage design, performances, appropriated architecture, printed matter, arrangement, costumes, etc., revolve around reversed epiphanies, hierophanies, carnival and similar Bakhtin-like narratives, all transposed into the profane, post-apocalyptic solitude of a former military base located in the grim Sudetenland.

In revealing the nature of the Cooperative’s work, we are challenged by several questions: At which point does authorship end and illusion, irony and theatricality take over? Are we witnessing genuine devotion, art and humility in the face of the transcendent, or are we instead dealing with an ironic, hebephrenic, compulsive defacement of all authorities, their myths, celebrations, and rituals? Is this some strange form of sectarian, fetishistic practice, or are we witness to a subversive grimness, similar to the heretical tradition that can be traced through the Grand Guignol, Alfred Jarry, Jaroslav Hašek, the Surrealists, Dada, and the iconoclasm of Punk?

I presume that in the case of the JSD Cooperative, the juxtaposition of the real and the ironic, of the sacred and the profane, will lead to some false assumptions. The dialectical cohesion of the serious vs. the grotesque are inseparable in the poetics and methodology of the construction of their whimsical and joyful universe. This universe consists of regular instances of ritual worship, the pseudo-fetishistic gathering and sacrificial burning of rubbish and scrap collected from the streets, the deconstruction and re-contextualization of an abundance of narrative phantasmagoria. These intertwine with the text of assemblages which represent the virtual tenants who inhabit the labyrinth-Merzbau of the Church of the Psychiatric Treatment in their small town.

Similarly, the Cooperative’s ambivalence toward seriousness and irony is captured in the rhetoric, jargon and style of the handmade samizdat editions of reports and manifestos, decorated with photographs, inserted and found objects, accompanied by a variety of ritual costumes. These vignettes and stories are distributed among initiated readers and at the events, gatherings, and occasional expeditions of the Cooperative’s community.

If one would like to designate a basic semantic gesture, an Opera Omnia blueprint for the prolific opus of the Peerless Cooperative of the Holy Nurture, a fitting candidate might be found in the metaphor of the assemblage, or bricolage, a cluster of hybrid objects trouvés, habits and scattered mycelium of meanings, inuendos and social links. 4

This artistic gesture can be described as a radical departure from the patterns of linear coherence familiar to us in the alienated channeled, machine-like grid of language and the Universalist canon of modernity.

Unlike the mainstream of the contemporary Czech visual art scene, the style of the Cooperative intuitively and deliberately resists current fashions, and rejects the ‘art world’ in general. However, their idiosyncratic receptivity to different aesthetic and historical styles is all-embracing. Regardless of their penchant for the dark realm of the obscure, the anomalous, the decaying, the Gothic, the literary, and their wide range of religious inspirations, the Cooperative looks from its very nature surprisingly traditionalist, even anti-postmodernist. Although it may sound like hyperbole, such features place JSD among the Czech and international pantheon of “genuine eccentrics”, mavericks, and “true artists” in an environment otherwise fueled with trendiness and snobbism.

Miloš Vojtěchovský

2008 — 2017

Literature

Mircea Eliade, “The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History”, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1971.

Walter Benjamin, “On Some Motives in Baudelaire,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, New York: Schochen Books, 1969.

Vladimír Borecký, Zrcadlo obzvláštního (z našich mašíblů), Hynek 1999.

“Notes on Art Brut in the Czech Republic,” Barbara Šafářová and Terezie Zemanková, Paris 2002.

Maurice Blanchot, Thomas the Obscure, The Negative Eschatology of Maurice Blanchot (http://www.studiocleo.com/librarie/blanchot/kf/abyss/the_sea.htm).

Dvacet let tajné organizace B. K. S., edited by Pablo Augeblau, Prof. Eckel Eckelhaft, Jirek Zlobin-Lévi Ostrowid, Dr. Škába Sklabinský, in Výtvarné umění, 1994, č.3

Pepperstein, Pavel: Prohlídka některých nových pamětihodností českého uměleckého života očima cizince. In Výtvarné umění: Umělecký měsíčník pro moderní a současné výtvarné umění 2/5 (1991), 23-47.

Gaston Bachelard: Water and Dreams, An Essay on the Imagination of Matter. Dallas: Pegasus Foundation, Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture, 1999, 1983. Czech translation: Voda a sny: esej o obraznosti hmoty, Praha 1997

Gillian Whiteley Junk: Art and the Politics of Trash, I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd. 2010

Georges Didi-Huberman: Ninfa fluida. Essai sur le drapé-désir, Gallimard, coll. Art et artistes, 2015/ česky Ninfa moderna.Agite/Fra, 2010

Footnotes

1. It is interesting to note that although artifacts made by JSD have been exhibited at numerous exhibitions and festivals (for instance at Školská 28 Gallery in 2007, or Four Days in Motion in 2009 and 2012, etc.) so far no one from the professional community has attempted to systematically explore, document and interpret their work within a wider cultural context. The absence of such theoretical readings prompts the author to sketch out at least some of the Cooperative’s artistic gestures, customs and meanings. ↩

2. As opposed to the affiliated organisation B.K.S. (Bude konec světa) [EIN (End Is Nigh)], the JSD does not reject contact with the public but rather encourages it. ↩

3. Apart from the already-mentioned B.K.S, we may find other affiliated groups, like the now-extinct Bratrstvo (Brotherhood). A direct connection with Czech art of the 1970s may be found in the figure of prof. Zdeněk Beran, the head of the Painting IV Studio at The Prague Academy of Fine Arts, with whom David Koutecký studied, or in their contacts with the underground film maker, writer and publisher Lubomír Drožď, aka Čaroděj OZ, Blumfeld S.M., Homeless & Hungry. In the 1990s, Pavel Pepperstein, the member of the Russian artist group Medical Hermeneutics (with Jurij Leiderman) published a text on collectives and "secret" societies in Czech contemporary art in the magazine Výtvarné Umění. * ↩

4. In the arts, bricolage (French for “DIY” or “do-it-yourself”) means “the construction or creation of a work from a diverse range of things which happen to b e available, or a work created by such a process.” And so a bricoleur is “a kind of handyman, who improvises technical solutions to all manner of minor repairs.” The term is frequent in different fields, including philosophy, critical theory, education, computer software, and economics. In the arts are many examples of a variety of approaches toward bricolage (or assemblage) in Dada, Surrealism, arte povera, and Fluxus; in the works of Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Cornell, Meret Oppenheim, Jean Tinguely, Josef Beuys, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Smithson, Edward Kienholz, Gordon Matta-Clark, William Burroughs, Nam June Paik, George Maciunas, Yoko Ono, and Thomas Hirschhorn, and Jason Rhodes; in the music of John Cage, Pierre Schaffer, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Frank Zappa; as well as in the literature of James Joyce, Jorge Luis Borges and Georges Perec. According to Claude Lévi-Strauss, there can be a mythical thinking described as a kind of bricolage. Similar concepts play a role in the work of Walter Benjamin, the Situationists, and the Structuralists, especially in the semiotics and the sociology of everyday of Michel de Certeau. The related ideas of Georges Bataille, Michel Leiris and Roger Caillois on bricolage were later appropriated in the French postmodernist and deconstructivist theories of Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard, Jacques Derrida, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guttari. The subversive function of bricolage also plays a role in the texts of contemporary authors and theorists, such as W.G. Sebald, Georges Didi-Huberman, Jacques Rancière, Nick Land, Sadie Plant and Tim Morton, among others. ↩

5."I have kept “living” proof of these events. But without me, this proof can prove nothing, and I hope no one will go near it in my lifetime. Once I am dead, it will represent only the shell of an enigma, and I hope those who love me will have the courage to destroy it, without trying to learn what it means. I will give more details about this later. If these details are not there, I beg them not to plunge unexpectedly into my few secrets, or read my letters if any are found, or look at my photographs if any turn up, or above all open what is closed; I ask them to destroy everything without knowing what they are destroying." in Maurice Blanchot’s Death Sentence (1948), https://monoskop.org/images/9/94/Blanchot_Maurice_The_Space_of_Literature.pdf ↩